A common business mantra stating that in order to succeed entrepreneurs must ‘fail fast and fail often’ is often not applied to those already working within a company. This is, as Ankur Jindal argues, a short-sighted approach for budding intrapreneurs.

When bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned from a holiday in 1928 to find mould growing on one of his petri dishes, he probably thought his experiment was destined for the bin. But when closer inspection revealed that the mould had inhibited the growth of bacteria around it, the most famous accidental discovery in history was born.

Penicillin was the first true antibiotic, heralding the start of a new age in medicine, but at first glance the circumstances surrounding its development were a complete failure. While the events that led to it might seem like a one-off, the lessons Fleming’s discovery teaches us about innovation are still relevant to modern businesses nearly a century later.

“Instead of treating unexpected outcomes as failures, learning lessons from mistakes and making them an acceptable part of an organisation’s culture can lead to the biggest breakthroughs of all.”

Penicillin wasn’t the first (or last) unintentional invention. Countless other everyday items have come about as the result of a happy accident, proving that sometimes failure is the path to success and exploring new paths can be beneficial to all – even when the results aren’t exactly as intended.

X-rays

In 1895, experienced German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen was alone in his lab experimenting with a Crookes tube – a puzzling device that emitted a strange glow when a large voltage difference was set between the anode and cathode inside it.

Röntgen realised that it was also giving off a new type of radiation that could pass through solid objects and make them appear transparent on a screen. When he held his hand between them, he could see the outline of his bones, changing the way doctors would evaluate patients forever.

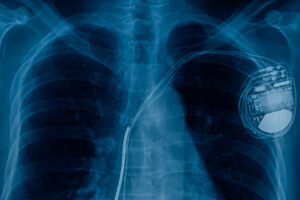

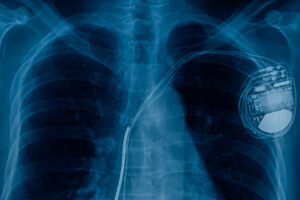

Pacemaker

One thing that will definitely show up in an x-ray is an implanted cardiac pacemaker, a life-saving device that was  also invented by accident. In 1956, American electrical engineer Wilson Greatbatch was building a device to record heartbeats, but after he fitted the wrong resistor it started to emit electrical pulses instead.

also invented by accident. In 1956, American electrical engineer Wilson Greatbatch was building a device to record heartbeats, but after he fitted the wrong resistor it started to emit electrical pulses instead.

Previous implantable pacemakers had failed after a matter of hours or days, making them impractical, but the mercury battery powering Greatbatch’s invention lasted up to two years, with further advancements increasing the lifetime of the devices – and by extension their patients – even further.

Super Glue

Super Glue has been accidentally sticking fingers together since 1958 but inventor Harry Coover first discovered its highly adhesive properties when he was trying to develop transparent plastic gun sights for Allied soldiers during World War II.

While it was too sticky for the army, Coover stumbled across the substance again nine years later when working on

a project to make heat-resistant seals for jet canopies, and its commercial potential was finally realised. Soldiers in Vietnam also used it to seal wounds on the battlefield, leading to a less toxic version being developed for medical use.

Microwave oven

The microwave oven has revolutionised cooking since its invention in 1946 – but it only exists because of a melted chocolate bar.

The microwave oven has revolutionised cooking since its invention in 1946 – but it only exists because of a melted chocolate bar.

Percy Spencer was an engineer working on radar technology at a company called Raytheon during World War II.

“While testing the power level of a magnetron tube one day he discovered his lunchtime snack had become a gooey mess in his pocket.”

After an egg he put underneath the tube also exploded, he brought in some corn kernels to pop and every lazy cook’s dream came true.

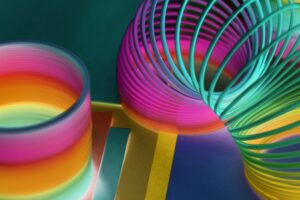

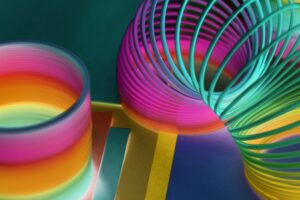

Slinky

Everybody’s favourite toy spring actually began life in the US Navy. In 1943, Richard James was working on a  system to stabilise a ship’s instruments in choppy seas, when he knocked a spring off a shelf.

system to stabilise a ship’s instruments in choppy seas, when he knocked a spring off a shelf.

Noticing how it neatly arced to the floor, the naval engineer thought he had the makings of a good toy. After deciding on 80 feet of steel coiled in a two-inch spiral, he had a local machine shop produce 400 Slinkys and put them on sale in a Philadelphia department store. They sold out in less than two hours.

The Slinky even had a second accidental use when soldiers during the Vietnam War used them as ultra-portable, hyper-extendable antenna for their radios.

“Some of history’s most life-changing inventions (and a classic toy) have come from those aiming for one thing and discovering another.”

Under different circumstances, these experiments could have been seen as failures, but with the right approach all became far more successful than ever imagined.

Failure is crucial to finding success – it’s how you deal with it when it happens that matters. That’s why Tata Communications created its Shape the Future initiative, which is designed to fan the flames of innovation and incubate the best ideas from within the company – with support to clear every hurdle on the way.

While organisations will always have key objectives to meet, fostering an environment of intrapreneurship and encouraging employees to experiment without fear of failure could lead to your business creating the next big thing – even if it does happen completely by mistake.

Read Ankur’s previous blog post about how to unlock innovation in middle management here.

Transformational Hybrid SolutionsOur cloud-enablement services offer the best performance on your traffic-heavy websites or mission-critical applications.

Core NetworksTata Communications™ global IT infrastructure and fibre network delivers the resources you need, when and where you need them.

Network Resources

Unified Communications As A ServiceBreak the barriers of borders efficiently and increase productivity with Tata Communications’ UC&C solutions.

Global SIP ConnectEmpower your business with our SIP network and witness it grow exponentially.

InstaCC™ - Contact Centre As A ServiceCloud contact centre solutions for digital customers experience and agent productivity.

Unified Communication Resources Case studies, industry papers and other interesting content to help you explore our unified communications solution better.

IoT SolutionsThe Internet of Things is transforming the way we experience the world around us for good. Find out more about our Internet Of Things related solutions here.

Mobility SolutionsTata Communications’ mobility services enable your enterprise to maintain seamless communication across borders, with complete visibility of cost and usage.

Mobility & IoT Resources

Multi-Cloud SolutionsWith enterprises transitioning to a hybrid multi-cloud infrastructure, getting the right deployment model that yields ROI can be a daunting task.

Cloud ComplianceCompliant with data privacy standards across different countries and is also designed to protect customers’ privacy at all levels.

IZO™ Cloud Platform & ServicesIZO™ is a flexible, one-stop cloud enablement platform designed to help you navigate complexity for more agile business performance.

Managed Infrastructure ServicesIntegrated with our integrated Tier-1 network to help your business grow efficiently across borders.

Cloud PartnersWe support a global ecosystem for seamless, secure connectivity to multiple solutions through a single provider.

Cloud Resources

Governance, Risk, and ComplianceRisk and Threat management services to reduce security thefts across your business and improve overall efficiencies and costs.

Cloud SecurityBest-in-class security by our global secure web gateway helps provide visibility and control of users inside and outside the office.

Threat Management - SOCIndustry-leading threat-management service to minimise risk, with an efficient global solution against emerging security breaches and attacks.

Advanced Network SecurityManaged security services for a predictive and proactive range of solutions, driving visibility and context to prevent attacks.

Cyber Security ResourcesCase studies, industry papers and other interesting content to help you explore our securtiy solution better.

Hosted & Managed ServicesTata Communications provide new models for efficient wholesale carrier voice service management. With our managed hosting services make your voice business more efficient and better protected

Wholesale Voice Transport & Termination ServicesYour long-distance international voice traffic is in good hands. End-to-end, voice access & carrier services which includes voice transport and termination with a trusted, global partner.

Voice Access ServicesTata Communication’s provide solutions which take care of your carrier & voice services, from conferencing to call centre or business support applications.

Carrier Services Resources

CDN Acceleration ServicesOur CDN Web Site Acceleration (WSA) solution helps deliver static and dynamic content, guaranteeing higher performance for your website.

CDN SecuritySafeguard your website data and customers’ information by securing your website from hacks and other mala fide cyber activities.

Video CDNDeliver high-quality video content to your customers across platforms – website, app and OTT delivery.

CDN Resources

Elevate CXIncrease customer satisfaction while empowering your service team to deliver world-class customer experience and engagement.

Live Event ServicesTata Communications’ live event services help battle the share if eyeballs as on-demand video drives an explosion of diverse content available on tap for a global audience.

Media Cloud Infrastructure ServicesTata Communications’ media cloud infrastructure offers flexible storage & compute services to build custom media applications.

Global Media NetworkTata Communications’ global media network combines our expertise as a global tier-1 connectivity provider with our end-to-end media ecosystem.

Use CasesUse cases of Tata Communications’ Media Entertainment Services

Remote Production SolutionsMedia contribution, preparation and distribution are highly capital-intensive for producers of live TV and video content, and their workflows are complex.

Media Cloud Ecosystem SolutionsThe Tata Communications media cloud infrastructure services offer the basic building blocks for a cloud infrastructure-as-a-service.

Global Contribution & Distribution SolutionsTata Communications’ global contribution and distribution solution is built to reduce capital outlay and grow global footprint.

Satellite Alternative SolutionsAs more and more consumers choose to cut the cord & switch to internet-based entertainment options, broadcasters are faced with capital allocation decisions.

LeadershipA look into the pillars of Tata communications who carry the torch and are living embodiment of Tata’s values and ethos.

Culture & DiversityHere at Tata Communications we are committed to creating a culture of openness, curiosity and learning. We also believe in driving an extra mile to recognize new talent and cultivate skills.

OfficesA list of Tata Communications office locations worldwide.

FAQCheck out our FAQs section for more information.

SustainabilityOur holistic sustainability strategy is grounded in the pillars of People, Planet and Community with corporate governance at the heart of it.

BoardHave a look at our board of members.

ResultsFind out more about our quarterly results.

Investor PresentationsFollow our repository of investor presentations.

FilingsGet all information regarding filings of Tata communications in one place.

Investor EventsAll investor related event schedule and information at one place.

GovernanceAt Tata, we believe in following our corporate social responsibility which is why we have set up a team for corporate governance.

SharesGet a better understanding of our shares, dividends etc.

SupportGet all investor related contact information here.